The State of Indigenous Treaties Around the World

Indigenous treaties have been a cornerstone of policy and governance in many countries, but their implementation and effectiveness vary widely depending on the nation and its specific history. In this article, we’ll explore the state of indigenous treaties in Australia, Canada, the United States, and New Zealand, highlighting successes and challenges.

**Australia: A Treaty-less Nation**

In Australia, a referendum was held to introduce a constitutional amendment that would recognize the rights of Indigenous Australians in parliament. The outcome saw 60% of votes against the Voice campaign, leading to a mourning period for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. While the country has a history of treaty discussions, no treaty between indigenous and the crown has ever been settled.

Instead, Australian Indigenous refer to 2017’s Uluru settlement, which reads at the bottom: “In 1967 we were counted, in 2017 we seek to be heard.” A successful Voice campaign would have been the first step towards the creation of a treaty. The current state of affairs is marked by frustration and disappointment among Indigenous Australians.

**Canada: A Constitutional Framework**

Indigenous treaties are constitutionally protected in Canada. Without these protections, it’s difficult for negotiations with the government to move forward. The country has over 300 treaties between individual tribes and the federal government. However, the relationship between Canada and its indigenous peoples is complex, with many tribes feeling marginalized and excluded from decision-making processes.

The United South and Eastern Tribes executive director Kitcki Carroll (Cheyenne and Arapaho) noted that the US-Canada treaty relationship is rooted in the two countries’ constitutions and laws. However, despite this framework, there are still significant disparities in access to healthcare, education, and economic opportunities between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples.

**United States: A Complex Relationship**

The United States has a complex and varied history of treaty-making with its indigenous peoples. The country stopped treaty making in 1871, instead relying on trust obligations to manage its Native American affairs. However, the relationship has undergone significant changes in recent years.

Kirk Francis, Chief at Penobscot Nation in Maine, said his tribe used to be treated as wards of the state, without access to basic services like running water and electricity until the late 1970s. The change has only happened within the past 45 years, with the tribe now having their own judicial branch, legislative branch, law enforcement, housing, education, and healthcare systems.

While Francis acknowledged that there’s still a long way to go, he noted that the relationship between his tribe and the US government is more collaborative than ever before. The tribe employs everyone working in those facilities, indicating significant progress in addressing historical injustices.

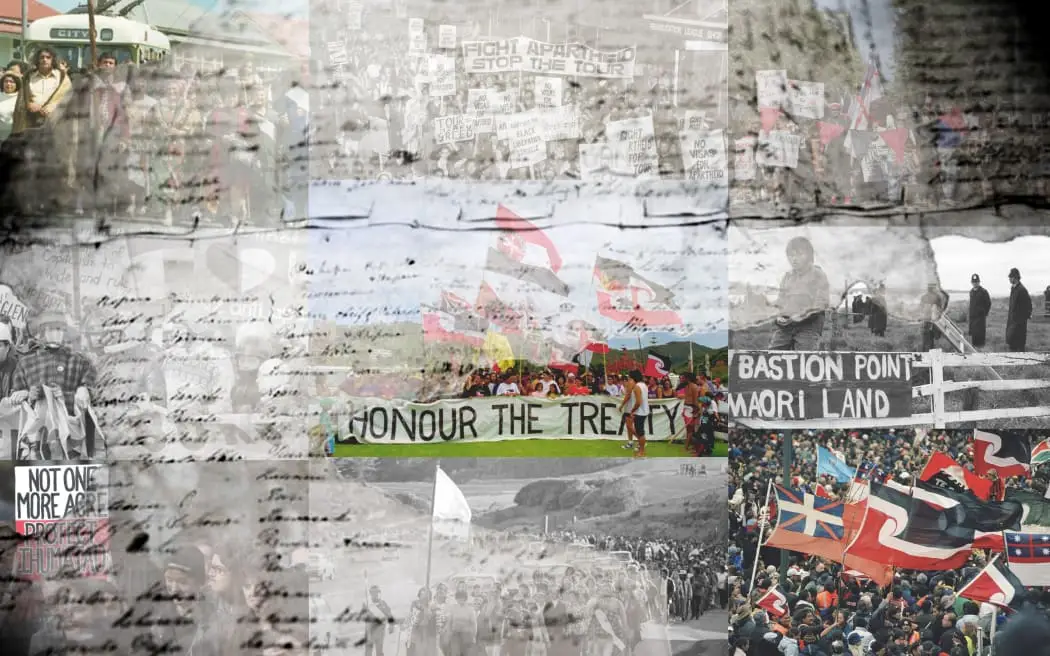

**New Zealand: A Mixed Legacy**

In New Zealand, the treaty between indigenous Māori and the crown has been in place since 1840. However, the country’s history of colonialism has left a mixed legacy for Indigenous peoples.

The ‘yes, or no’ tick box on the 2020 Australian referendum was seen as an opportunity for New Zealand to take steps towards reconciliation with its indigenous Māori population. The outcome saw 56% voting in favor of the Voice amendment, which would have recognized Indigenous rights and powers in parliament. However, it is unclear what specific provisions were included or how they will be implemented.

**Conclusion**

The state of indigenous treaties around the world highlights both successes and challenges. While Canada and the United States have established frameworks to protect Indigenous rights, Australia and New Zealand face significant hurdles in recognizing their treaty obligations.

In conclusion, acknowledging and addressing historical injustices requires ongoing effort and commitment from governments and civil society. It is essential that we learn from each other’s experiences and work towards a future where all peoples can thrive together.

0 Comments